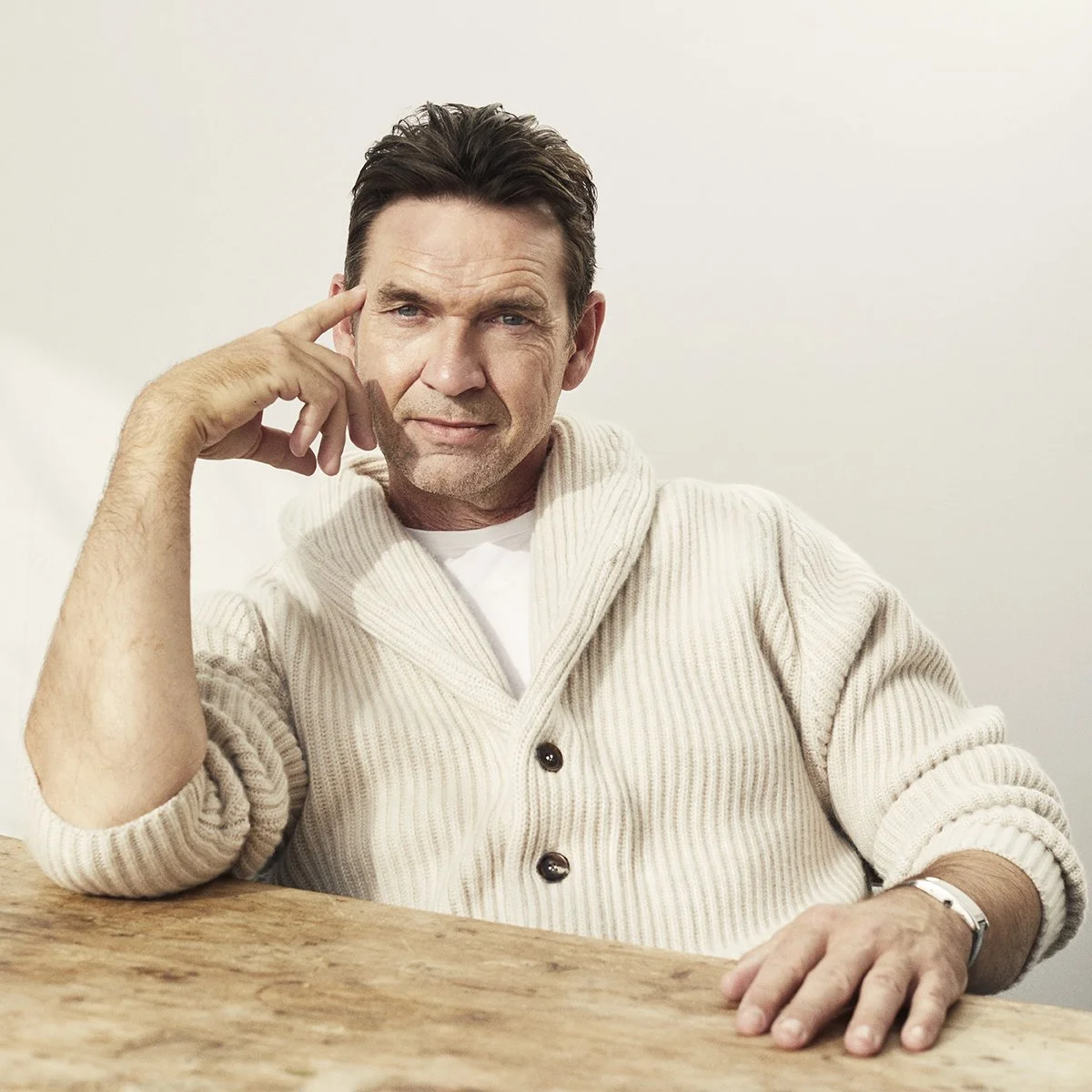

Dougray Scott relishes latest Machiavellian role.

Image: David Reiss.

Since starting out in theatre in the 1990s, Dougray Scott has appeared in a diverse portfolio of films and television, from blockbusters like Mission: Impossible 2 to acclaimed, small-budget productions such as Last Passenger, from glossy American series Desperate Housewives to adaptations of literary classics Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and The Day of the Triffids. This winter he can be seen as Air Marshall Marcus Grainger in the second series of hit TV show Vigil.

“He’s Machiavellian, he’s a maverick in some respects, but you can’t quite pin him down, and I think that you shouldn’t really be able to,” is how Scott describes his character. “I’ll tell you one thing that remains true throughout the whole course of the episodes is that he’s very, very patriotic. He loves his country, and everything that he does, he does for the benefit of the people of Great Britain.” Written by the “phenomenal” Tom Edge, the new series is an exploration of the arms trade and its importance to the UK’s influence in the Middle East, a subject that Scott found fascinating. He explains that an economic relationship founded on the sale of weapons is seen by the government as stronger than any cultural or diplomatic ties for keeping a British foothold in a volatile region. “I enjoyed the politics of it. I was interested in how it would unfold within the story of Vigil.”

Scott has a genuine and wide-ranging curiosity about things that lie outside his immediate experience, which makes researching roles a significant perk of the job for him. “You get to see aspects of our history and of our world; you’re educating yourself about different things.” For Ripley’s Game he learnt his craft from a professional picture-framer in Chelsea and for Enigma he met leading mathematicians in Cambridge and visited Bletchley Park to understand the mechanics of code-breaking. “I’m dyspraxic so figures to me are alien, I have a very different approach to things, and people despair of me trying to figure out mathematical problems. But that was fascinating when it was explained to me how the code-breaking worked. And also getting to hang out every day on set with Mick Jagger [who produced the film]! That was surreal but exciting because he’s like, ‘Come and play some music’ – I end up with Mick Jagger in his room playing these new tracks. So that experience was pretty special.”

“My intention has always been to feel rather than to act, and to not have to think about it. All the research you do, when you get to film it, you just forget about it; it’s part of you by that time”

Research for his part in Irvine Welsh’s Crime, which won him an Emmy last year, has taken him to some bleak places. Although Scott enjoys playing lighter roles in films such as A Town Called Malice and This Year’s Love, he admits to being “drawn to the darkness. It feels familiar to me, and I think it’s maybe a more authentic depiction of the world.” But the big attraction of Crime was the opportunity to work with a writer he has long admired. “When I read Irvine Welsh, I just was so blown away by the fact that there was no barrier, there was no ocean to cross. I just thought, I’m looking in the mirror and he’s writing about my world, in my vernacular – that’s what made it so exciting and extraordinary, as a young man, to read that kind of writing. So when we talked about doing something together, I was like, ‘Well, this is just nirvana for me, to work with the writer that I probably most admire.’” Scott also sees similarities in their approach to character. “Irvine doesn’t judge: he presents the world as it is, and it’s what I try to do as an actor. You try and find the flaws in the good people and redemption in the bad people, and then you get a well-rounded, authentic, relatable character.” This again comes down to research for Scott, however unappealing it may be at times. “Waking up every morning and looking at documentaries of Robert Black I would say is not healthy for the mind, but you need to be connected to it in order to understand, when the cameras roll, that you’re there, it’s you. My intention has always been to feel rather than to act, and to not have to think about it. All the research you do, when you get to film it, you just forget about it; it’s part of you by that time.”

Image: David Reiss.

Scott has thought of acting as a bridge to other worlds ever since his stage debut in a school performance of Tennessee Williams’s Suddenly Last Summer. “It was probably a terrible production, but I was fascinated by the connection between actor and script – how it could transcend continents and countries, cultures, class, and somehow make sense to different people. I read Arthur Miller as well [who he was later to play, in My Week with Marilyn] and I was struck by the power of writing, and the ability to emotionally affect another human being and help you see the world through their eyes. Also, it made the world a lot smaller for me: it made me realize that actually we have so much more in common than we have differences in the world. We have different cultural experiences, we have different political systems, but ultimately, I think, as human beings we search and expect and desire and hope for the same things, whether that’s love, relationships, professions that we’ve decided to go into, what we are drawn to, what fascinates us, what inspires us.”

As twentieth-century American drama gave birth to his love of acting, it’s fitting that the most personally fulfilling theatre performance of his career was in Lindsay Posner’s recent production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? opposite Elizabeth McGovern. “It felt good, it felt alive. Throughout the course of rehearsals, we discovered slowly that we both had a connection with the characters. Lindsay was brilliantly meticulous with his demand that we stick exactly to the language, because if you miss a beat, a pause, a comma, a silence, everything falls apart. With Edward Albee, you need to adhere really closely to the script because through that you discover the rhythm, and that gives you a portal into the character and into their world. So I would say that is my most enlightening, satisfying experience of theatre.”

Scott still feels the exhilaration he first encountered as a teenager acting on stage, although he admits that it’s “fucking terrifying” compared with film work. “I mean, you get nervous when you start doing a movie but still you can do it again if you get it wrong. But in a play you are there, the audience are there and there’s no going back. It’s all about how you approach that opening night, how you manage to focus your nerves, how you manage to use them to the positive effect of the production. So there is nothing else like it and, for an actor, when it works it’s the best feeling in the world.”

Vigil begins on Sunday 10th December.

Author: Rachel Goodyear